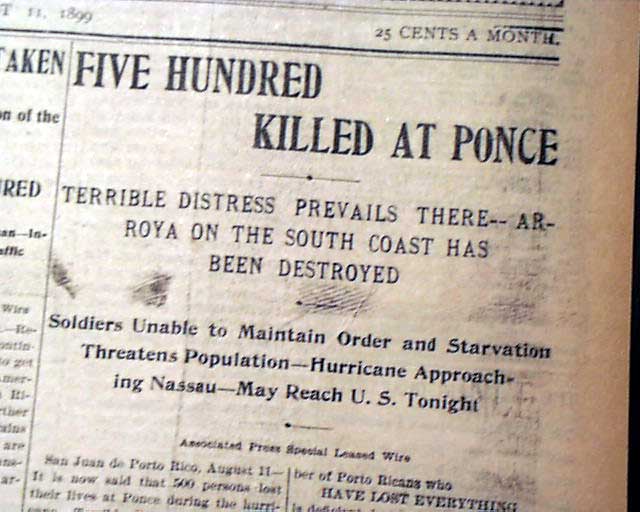

On August 8, 1899, hurricane San Ciriaco destroyed the majority of the crops, thousands of peasants’ dwellings, and killed roughly 3,400 Puerto Ricans. Relief efforts started before San Ciriaco. Though the U.S. Army occupation forces in the island immediately engaged in relief missions and tried to reestablish order- the situation deteriorated.

In December 1898, the American military governor, Guy V. Henry had requested from Luis Muñoz Rivera, acting civilian secretary, a report detailing “any cases of poverty or destitution which cannot be relieved by the inhabitants of the place” with the intention “if possible, to help these people” in recognition of the poor condition in which the majority of the countryside folks lived. San Ciriaco just worsened the condition of the Puerto Rican peasantry.

It was during the relief effort after hurricane San Ciriaco castigated Puerto Rico in 1899 that a U.S, Army junior medical officer discovered the cause of chronic anemia- the worst ailment afflicting the Puerto Rican peasantry in the nineteenth and early twentieth century.[i] The parasitical intestinal hookworm known as ancylostomum duodenale was responsible for the anemia that made the peasant folk look emaciated, decades older than they were, and condemned them to a very early death.

While in charge of the medical detachment in Ponce, Captain Bailey K. Ashford, a U.S. Army doctor, realized that the poor physical condition of the Puerto Rican Jíbaro, was not due to the climate- as the entrenched local medical class insisted. How could it be? How could the weather selectively target only the peasantry?

Ashford had felt a mixture of guilt and a drive to find the cause of the so-called “chronic anemia” that seemed to plague the Puerto Rican peasantry- the jíbaros– after the U.S, military had opened the doors of the old Spanish military forts to house the displaced Puerto Ricans and set up field hospitals to treat the ill and sick- just to witness wave after way of emaciated ghoulish peasants coming to the forts and hospital and soon die before the perplexed American soldiers and medical personnel.

Blood samples had not yielded any results. Looking a “thin film of feces crushed between cover glass and glass slide” Ashford noticed an “oval thing with the four fluffy gray ball inside”. It was a worm egg. After consulting Manson’s Tropical Diseases- he had found the culprit. The parasite had previously been found among anemic Italian miners who had worked in the construction of the St. Ghotthard tunnel in Switzerland.

Ashford had a realization- he had seen the same symptoms among the destitute peasantry in Mexico, Central America and the “old Spanish Main.” He believed that they suffered from the say- but would have to prove it. After all- he was a doctor and a scientist.

So, he proceeded to administer the remedy -Thymol- to a Puerto Rican Jíbaro affected by the “anemia.”

The Jíbaro had just became patient zero in the first salvo against a malady affecting millions of peasants throughout the Caribbean and Latin America.

On November 24, 18998 he telegraphed:

CHIEF SURGEON, SAN JUAN

HAVE THIS DAY PROVEN THE CAUSE OF MANY PERNICIOUS, PROGERSSIVE ANEMIAS OF THE ISLAND TO BE DUE TO ANCYLOSTOMUN DUODENALE.

ASHFORD

Before Ashford was able to complete his study and convinced the criollo and Spanish medical establishment that the Puerto Rocan peasantry could be cured of their “anemia”- he received orders for a new post- the Philippines. He had in fact found close doors and even animosity both from the local medical establishment and the towns’ patriarchs. And now, the military was posting him far away from the front lines against the anemia cripling millions of peasants.

Luckily for the Puerto Rican peasantry, the orders change at the very last minute, and he was sent instead to New York.

Ashford completed his study and found the cause of the Puerto Rican’s chronic anemia while stationed in David’s Island (Fort Slocum) in New York. He visited the nearby Museum of Natural History in Glen Island (on the Long Island Sound).

The museum had living exhibits. Humans, thought as rustics or savages brought from all parts of the empire to carry out mundane tasks as Euro-American crowds observed them. Just as humans observe animals at a modern zoo.

In this human zoo, Ashford found a “colony of Puerto Ricans, living as they lived, in their little thatched houses, and making the so-called “panama” hats. These jíbaros were from Cabo Rojo… And they all had hookworms”

He tested and treated them, and presented his findings at the Westchester County Medical Society. From this point onwards, Ashford would redouble his effort to treat the Puerto Rican peasantry.

Ashford had found that the worm Ancylostoma duodenale was the cause of the epidemic anemia in Puerto Rico. The remedy was simple enough; purging the parasites by administering the patients a concoction of Thymol-a phenol found in the oil of thyme- diluted in alcohol.[ii]

The island’s medical establishment had long argued that the chronic anemia, or “laziness,” affecting the peasants, which was responsible for one third of all deaths in Puerto Rico, was due to the climate, nutrition, bad hygiene or malaria, or a combination of these factors, and as such, it was endemic in the mountains and coastal plains where the Jíbaro lived.

Ashford recounts that when asked how their relatives had died, most peasants would respond, and physicians would confirm: “De la anemia-la muerte natural, of anemia-natural death”.[iii] His wife, who came from prominent criollo families, explained to him “… that is the anemia of the country. They all die of it eventually.”[iv]

Ashford could hardly believe that a whole “agricultural class” was dying of anemia.[v] He was dumbfounded by the upper classes’ lack of interest in treating such a preventable and curable disease. After years of trying to persuade the medical establishment to adopt the relatively easy cure for pandemic anemia, Ashford was finally able to secure the creation of the Porto Rico Anemia Commission with a budget of 5,000 U.S. dollars in 1904.[vi]

After initially setting up the anemia camp in Bayamón, Ashley decided to move to Utuado, almost at the center of the island but with roads connecting to the Northwest, so those more in need of treatment could reach him. That first campaign treated 5,490 patients.

For the year 1905-06 the Anemia Commission moved its base to Aibonito, another mountain town but near the southeast.[vii] By the end of the second year the Commission had treated 170,000 patients, and the death rate had been reduced to .12 of one percent for those treated. Deaths from anemia fell from 11,875 in 1900-1901 to 1,758 in 1907-1908. The campaign lasted seven years. Between 1904 and 1911 over 310,000 people were successfully treated for the anemia.[viii]

Ashford also discovered that if the cause of the anemia was parasitical, it was severely aggravated by the peasants’ malnutrition. He recommended that socio-economic problems such as extremely low income, which he believed accounted for malnutrition and ignorance plaguing the Jíbaro, should be addressed to finally eradicate once and for all preventable diseases crippling the Puerto Rican peasantry.[ix] Only that way, he believed, would the Jíbaro awaken from his long sleep and small world and become an integral part of Puerto Rican society.

“Yet this is the man of whom we have to make a citizen, a man with a vote and a say in the affairs of the island. He has been through the awakening of Rip Van Winkle, and he has awakened into a world that leaves him gasping, stunned. He is neither a degenerate nor a fool”[x]

Adopting a paternalistic stance, the U.S. military establishment in the island, from infantry to medical officers, took the Jíbaro as a ward to be protected, and reshaped.[xi]

A special relationship between the U.S. military and the peasantry started to develop during the early days of the American occupation as a result of the relief efforts and sanitary campaigns launched by the military government.

As discussed by historian Estades Font, the motives behind such practices were not exclusively humanitarian. She explains that controlling tropical diseases was economically and militarily vital for American expansion. The labor force of the new territories, the occupation troops, and the civilian population of the mainland needed to be protected from such diseases.[xii]

Local elites also benefited from these health campaigns. After compiling the planters’ answers from a survey, Ashford argued that the planters estimated a gain of 61% in workers efficiency.[xiii] A planter from Aguadilla wrote to him that:

“I have observed that some of our peasants at a certain period of the year were left completely without support, for this terrible disease prevents them from working, and they had to beg in order to live. To-day, however, after cure of their anemia, they [the peasant and agricultural workers] own something -a little business, a cow, a nice little house, and, in addition subsist happily and work constantly.“ [xiv]

Though initially the condition of the Puerto Rican peasantry improved under U.S. sovereignty, the following decades would not be kind on them. As the infant mortality rate decreased and longevity increased, the emphasis on sugar cane production would lead to the pauperization of a malnourished, cyclically unemployed and abused peasantry.

This first intervention wrought tremendous changes in Puerto Rico.

_______________________________________________________________________________

[i] On August 8, 1899, hurricane San Ciriaco destroyed the majority of the crops, thousands of peasants’ dwellings, and killed roughly 3,400 Puerto Ricans. Relief efforts started before San Ciriaco. In December 1898, the military governor, Guy V. Henry had requested from Muñoz Rivera a report detailing “any cases of poverty or destitution which cannot be relieved by the inhabitants of the place” with the intention “if possible, to help these people.” Henry to Senor [sic] Munoz [sic] Rivera, December 12, 1898, AGPR, Caja, 135.

[ii] Ashford, A Soldier in Science, 3-5.

[iii] Ashford, A Soldier in Science, 3.

[iv] Ashford, A Soldier in Science, 42-45.

[v] Ashford, A Soldier in Science, 42-45. As his tests showed, it was anemia indeed as the white corpuscles in blood known as eosinophiles which should not exceed four percent were running up to forty percent in the blood of the peasants he sampled.

[vi] Ashford, A Soldier in Science, 56.

[vii] Ashford, A Soldier in Science, 68-70.

[viii] In Ashford’s account that number represented “1,600,000 visits over mountain trails and hot coast-lands to see the doctor.” Ashford, A Soldier in Science, 82-83.

[ix] Ashford, A Soldier in Science, 77, 79-80.

[x] Ashford, A Soldier in Science, 92.

[xi] The military paternalistic approach to the new colonial subjects was not restricted to Puerto Rico. It was also applied to the Philippines. See, Hawkins Making Moros, 5-6, x-xi. And, Go, “Chains of Empire,” 334. And Wintermute, Bobby A. Public Health and the U.S. Military: A History of the Army Medical Department, 1818–1917. New York: Routledge, 2011.

[xii] Estades Font, La presencia militar de Estados Unidos en Puerto Rico, 101; quoting President McKinley’s second annual message of December 5, 1898.

[xiii] Ashford, A Soldier in Science, 91.

[xiv] Ashford, A Soldier in Science, 91-92.